References 参考文献

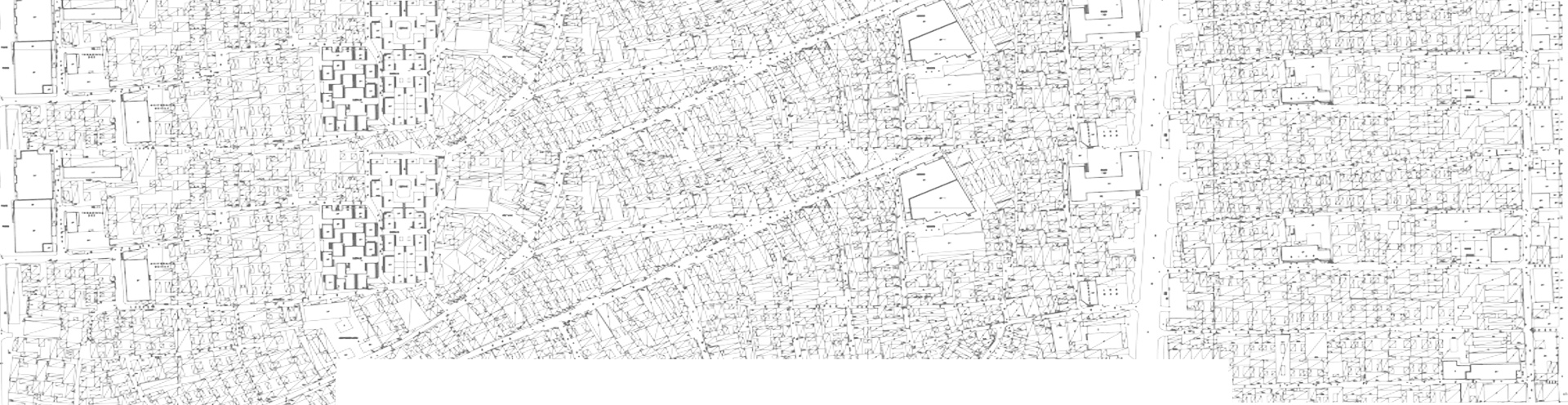

1. INTRODUCTION 1.1.Contextual Background It is commonly agreed that research on Domestic Space is a highly complex topic which demands a multidisciplinary approach. Studies on the mutual relationship of physical and socio-cultural factors in the construction of domestic space, are still quite rare and, above all, lacking the exploration of a methodical framework of analysis. Several authors have pointed out that lack of studies which relate architectural, cultural, social, political and individual underpinnings of the domestic space (Mary Gauvain 1982, Bailey 1990, Després 1991, Hanson 1998, Cieraad 1999, Lane 2007, Coolen 2008). For Hillier and Hanson (1987, pp.197) the main reason for this situation lies in the fact that traditionally, architectural research comes in two kinds: the kind concerned with architectural form and the kind concerned with behavior. Studies concerned with architectural form focus on the physical structure, construction, materials and technology while studies concerned with behavior, place emphasis on meaning at the expense of architectural variables. Despite the relevance of each approach, ifstudied separately, is very difficult to understand how specific design decisions may be determined by socio-cultural factors and might affect the behavior of the users. If research on domestic space is not able to pinpoint how space affects and is affected by social forces it invalidates any argument aiming at supporting design decisions from a social perspective. This problem is considerably aggravated if we consider how housing studies have contributed to the establishment of design guidelines for government housing based on the assumption that it is possible to isolate and identify common characteristics that house design needs to respond to in order to better serve users, normally translated into a hierarchies of spatial distribution within the domestic space from the exterior and within the dwelling. These assumptions were created by formal proposals (Alexander 1970, Newman 1972, Alexander 1977) eventually translated into standard plans and abstract checklists. (Julienne Hanson 1982, pp.6, Allen 2009, pp.55). According to Hanson (Julienne Hanson 1982, pp.6), the main problem with this assumption is that it completely ignores findings of ethnographic studiesin domestic space organization, which suggeststhat space is a reflection of social and cultural norms, not merely determined by human needs but also by the way it transmits social meaning. Allen (2009, pp.55) on the other hand, criticizes social sciences studies on housing, specially, existential phenomenology, for ignoring local knowledge - the observation and quantification of current housing conditions and resident’s satisfaction and behavior towards domestic space. Few studies focus on the evaluation of the social adequacy of the domestic space and the potential satisfaction of residents, using research tools from different areas of knowledge (Julienne Hanson 1982, C. Asli Sungur 2003, Cristiana Griz 2015). The majority of research on the relationship between domestic space configuration and residents’ behavior and satisfaction continues to pend towards a unidirectional analysis focused on space configuration analysis (Ana Silva Moreira 2017, Franciney Carreiro de França 2017) or empirical observation and collection of data in situ (Kellett 1991, Claude Lévy-Leboyer 1993, Moira Munro 1999, Hakky 2012, Joseph Agyei Danquah 2014, Shiva Ajilian Momtaz 2016). The paper is part of an ongoing research which attempts to conceptualize and define a methodology for evaluating the social adequacy of domestic space using a combination of qualitative and quantitative measures in a comprehensive approach to the evaluation of the complex relationships between space configuration and user behavior. 1.2.Subsidized Housing Program in Bahrain The selected sample for application and analysis of the developed methodology is the subsidized housing production of the Ministry of Housing of the Kingdom of Bahrain (MOH). The accelerated economic development unleashed by the discovery of oil in the region (Bahrain, 1932) was followed, almost immediately, by demographic growth, mainly due to the flock of foreign workforce to the region. This exerted enormous pressure on the existing urban structures, at the time,

composed of small villages and trading ports supported by the British Persian Gulf Residency, establish in 1763 to control trading activities with India. The new development pace was tackled by local governments in the form of welfare mechanisms (1950’s onwards) mainly focused on enhancing housing conditions for local citizens. The housing solutions were often materialized in the form of the single family house built in new suburban areas because the old city centers were considered too dense and unhealthy but also, because of the potential value of the land for non-residential purposes (Karimi 2016, Ragam 2017). Under British advice, the new urban landscape, followed Western construction methods and standards, completely detached from the local population(Adel Muhammad 2016, pp.6) and mainly influenced by the first oil-company towns in the region. In response to the demographic growth, the Ministry of Housing in Bahrain (MOH) established in 1975, affordable housing programs to aid its citizens in the acquisition of private houses. A new landscape was created in the country: numerous suburban developments (new towns) were built with specific legislation and a main goal to ensure the minimum standards of quality, suitability and comfort to local families are met. In 2012, the Bahraini government announced the construction of 40.000 units by 2022 in a series of large-scale projects. This solution means an increase of the existing housing stock by 25%, housing approximately 200.000 Bahraini citizens (a fifth of the Bahraini national population), an effort equal to the last forty years of government-built housing. If we add to these plans the existing MOH housing stock, approximately half of the Bahraini population will be living in government-built housing and largely in one of a few variations of a single housing typology; the landmass will have increased 20% and 28% of all urbanized area is built by MOH (Karimi 2016, pp.45). The moment houses are delivered to its residents a continuous process of transformation begins. The motivations behind it may vary as well as the outcome but the mentality behind is the same: a need for distinction and adaptation. Before this scenario of mass production of houses for Bahraini citizens it is imperative to attempt to evaluate the suitability of the domestic space to the behavior of the its users. 2. DATASETS AND METHODS The sample for analysis consists of eleven housing projects built by the MOH between 2012-2016, evenly distributed geographically throughout the territory. In each housing project 10 houses were selected randomly to perform the analysis of resident’s relationship with the house, mainly their level of satisfaction and alterations performed. This paper presents the results for one of the housing projects – Samaheej, Muharraq. In order to understand if the behavior of residents towards their dwelling, is a reflection of functional needs or social pressure; and, the extent to which, spatial configuration is affecting behavior, the methodology is composed of three procedures: 1. Residents Mindset: on site observation and semi-structure interviewsto residents with the main goal of collecting personal info, educational and economic background, daily habits and routines, overall level of satisfaction towards the house, alterations and reasons behind; 2. Function and Meaning: geometric and functional analysis. It is commonly assumed that alterations made to the domestic space are mainly related to functional needs. However, if we also accept buildings as devices that reproduce social structures and meaning (Amorim 1997), sources of information about the societies which created them (Hanson 1984), it is important to evaluate the motive behind different types of alterations: pragmatic nature (family size, economic constraints, specific functional needs) or responding to psychological pressure of the individual before society; 3. Configurational analysis of original and altered houses: the comparison was based on the analysis of the justified access graphs, levels of depth/integration; visibility/permeability; transition-space ratio, rings-sequence ratio, and symmetry for the original dwelling and the altered houses.

Configurational descriptions help to determine how a system of spaces is related to form a pattern, which is independent from the intrinsic properties of the individual spaces themselves. Justified access graphs are a simple way to visualize configurational differences in buildings. The graph is aligned bottom-up from a starting node, called root (the outside or any otherspace), the nodes directly connected to the root (i.e. with depth 1) are aligned horizontally immediately above it, then the nodes directly connected to the former set (i.e. with depth 2) are aligned in the same way, and so on, until all levels of depth from the root are accounted for. This allows us to understand how distant, in topological terms, each space is from the root (depth), as well as how spaces relate to each other. (Hanson 1998, pp.27). The spatial configuration was also analyzed in terms of sectors structure. According to Amorim (1997), a common approach to architecture design is to classify and group domestic activities into functions. These are then arranged in relationships and hierarchies according to what is consider the ‘right way of living’. The ‘sectors graph’ allows for a clearer visualization of the location of different functional sectors(sleep/bathe;social visitors and family;service, and mediatorspaces) in the spatial configuration (segregation or permeability) and the relationship with each other (Cristiana Griz 2015). As the justified access graph, spaces grouped into functional sectors are aligned bottom-up from the root, resulting in a simplified graph which reveals the essence of the relationships of functional sectors from the root and between each other. This proves to be particularly helpful in the analysis of altered houses. Previous ethnographic research and interviews results revealed that Bahraini society is highly structured and concerned specifically with the inhabitant-visitor, male-female relation, which leads to a specific categorization of functional sectors (Furtado 2017). In order to better understand the dynamic between the family and visitor realms in the Bahraini house, we explored the concept of the ‘integration core’ and ‘hub and anchor’ (Alice Vialard 2009). According to the authors, the shape and location of the integration core of the houses reflects its level of formality. The core is composed by the 3 most integrated spaces of the house. Within the integration core we can distinguish two types of spaces, the ‘hub’ is the space with the greatest degree of connectivity – the most public space of the house; while the ‘anchor’ is the most integrated space, the core of the house. The measure of depth of these 2 spaces within a house from the entrance (the distance of the public core from the center of the layout), reveals the level of investment in privacy amongst its inhabitants and in separation of activities. The MOH houses have generally a tree-like structure, segregated and deep, and the most integrated space is the living room, located in the center of the house, connecting all functional spaces (a functional and connector space). It is important to investigate if in the altered houses the depth of these spaces varies in relation to the overall layout. Another important measurement is the level of distribution and symmetry, dimensions that reveal the level of choice and permeability of a layout. The exiting house is a transition-integrated complex, which means the layout uses transition spaces to isolated inhabitants and frame behavior, and very few rings to offer choice. These two parameters are measure in the altered houses. Spatial configurations can be made up of four topological space-types normally represented with letters - ‘a’, ‘b’, ‘c’, ‘d’ – where, ‘a’ are terminal spaces, static in nature; ‘b’ spaces are thoroughfares on the way to a terminal space, where movement is still highly directed; ‘c’ spaces have more than one link and can be crossed, part of a single ring; and ‘d’ spaces have more than 2 links part of more than one ring which generate choice (Hanson 1998, pp.173). Space-types represent structural dimension of spaces. Dominant space-types within the system support the measurement of key spatial characteristics of buildings layouts such as transition-space ratio, ring�sequence ratio, symmetry and asymmetry (Hanson 1998, pp.173). The transition:space ratio (i.e. their count divided by the total number of spaces), measures the economy or insulation of the layout independent of size (how much spaces are placed in continuous sequence or separated by transition spaces), allowing for the interpretation of spatial patterns as a product of social practices, unaffected by economic constraints. Transition spaces may be used to a greater or lesser extent to separate and insulate activities and people from one another or draw them together respectively. A predominance of ‘a’ and ‘b’ space-types emphasize tree-like configurational properties, because such spaces offer no route options, strongly framing the activity of its occupants and, therefore more segregated and non-distributed, whilst the predominance of ‘c’ and ‘d’ space-types are conductive to ringiness, which give people choice and is therefore, more permissive and distributed. According to Hanson (1998, pp.188) the transition:space ratio allows the understanding of the distributedness of plans (or the ability of space configuration to bring people together or isolate them): (a+b)/(c+d) equals distributedness, where a low value is distributed and a high value is non-distributed. The ring:sequence ratio measures asymmetry which expresses the houses potential to differentiate and express distinctions of personalities and social situations: (a+d)/(c+b) = asymmetry, where a low value is asymmetric and a high value symmetric.

发表于 2020-12-09 01:04

发表于 2020-12-09 01:04

收藏

收藏  支持

支持  反对

反对  回复

回复 呼我

呼我 支持

支持 反对

反对